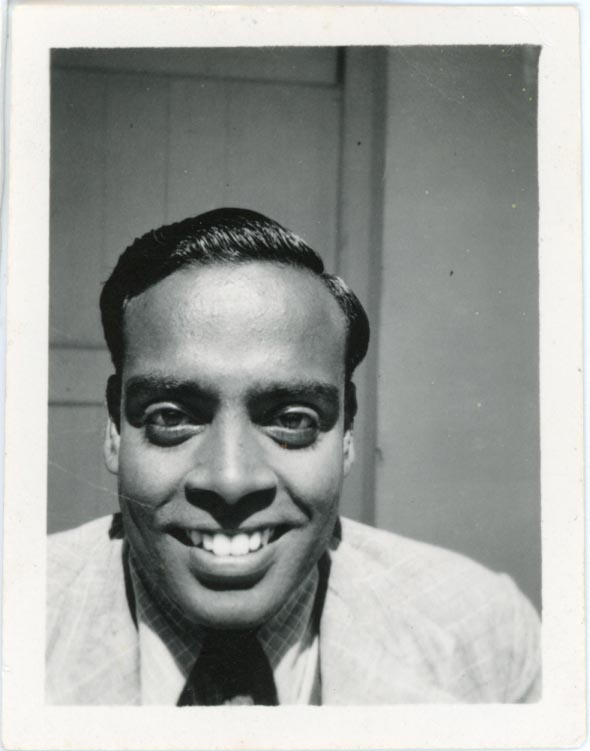

S.S. Gopalkrishnan

From the Paul Brunton Archives

A strange fate once threw me into a peculiar position-a position from which I took note of the chief happenings in the inner lives of a few American and European brothers and sisters who were striving hard to learn and understand the highest truths of Indian and Yoga and Eastern philosophy under the excellent, noble and clear guidance of a unusual master, who now and then disowned his mastership and buried himself in the hollow of the Pyramids or hid himself in the remotest villages of the Far East, or again ascended and lost himself in the freezing colds of the peaks of the highest mountain range. I refer to the one who was equally on close friendly relations with the matted-haired yogi, or the Egyptian bushy-bearded Muslim, or the shaven-headed Supreme Lamas in China and the Buddhist countries.

I am not a biographer, and so the reader will have to excuse me if he finds this to be scrappy, disjointed and broken. For my part I will be quite satisfied if this makes interesting reading and describes a few salient happenings and incidents which help to reveal, though in a poor way, this amazing person. I met him by a strange coincidence. Coincidence indeed, apparently, but really the strong hand of good karma that made me cross his path. When low in spirits, having been the victim of a big bank crash in South India, in which I had invested money and where I was employed as a subordinate officer, and having wife and children to support. Spiritually jaded and exhausted in the maze of conflicting faiths, beliefs, and opinions, I read A Search in Secret India; it exerted a peculiar influence over me. Day after day the influence it had on me grew more and more until at last I could no longer resist the temptation of meeting its author. But as that book ended with his return to his native West, I erroneously thought he was still there and regarded such a meeting as impossible.

After the above preface you will not be surprised if you find yourself suddenly transported to a small country town in southwest India. The reddish roads are marked by their dusty quietness. Except for a bullock cart or two, and odd villagers slowly passing occasionally, or the hurrying past of a stray cross-country motor bus, there is nothing to be seen or heard. The gentle breeze rustling through the leaves of coconut palms which line the road on one side at different points adds to the completely rural atmosphere. There is some sign of activity only in the main bazaar street. Coolies trotting with their baskets poised over their heads, a few villagers looking with open mouths at the display of dirty oil-fried cakes, the masses of yellow mangoes and brown berries both ripe and unripe heaped in groups on the floor of the fruit-stall, clamorous haggling of the booth-keepers, the noise of the harsh music of the gramophone-record through the prehistoric horned instrument, the rattling of the tin pots of the tinker, the sonorous hiss of the hand blow-pipe of the smith, are the common sights and sounds that present themselves to you.

A certain spring day, when I happened to visit this little town for the first time, was, is, and will be the most memorable throughout my life. Looking back now, I find how plainly all events and circumstances and environments joined together to bring this visit about and also how everything that has developed since then roots in it as the most blessed day of my life. By a mysterious event, the very same day that the globe-trotter himself came back to India, an unusual force pulled me forcibly and I travelled about 300 miles away from home unconsciously to the same destination. Just as I was getting into a bullock cart to proceed to the railway station, which was a couple of miles away, I heard the cart-driver conversing with another man. The word “Brunton” was mentioned in the conversation. I immediately questioned the driver about it and was astonished to hear that he had the honour that very morning of carrying the famous writer to a house he had engaged on his return to India. I postponed my journey to the station and was driven to his house instead.

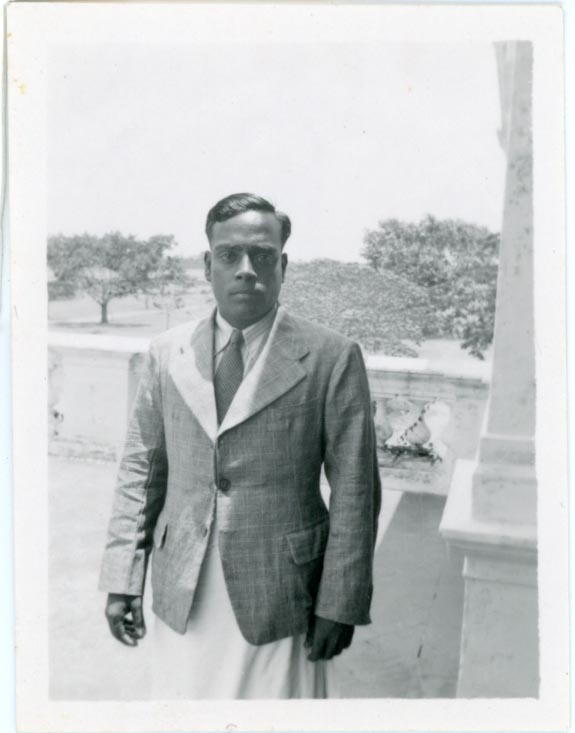

I introduced myself to Dr P. Brunton, and simply said that I was pleased with his book, a native of the historic temple-city of Madura in south India, and that I had had the good fortune of a college education in the missionary college there. I also stated that my grandfather had been one of the great Sanskrit pandits of his day, though I knew but little of that language. No boots, no socks, no coat, no tie or bow, and no hat were found on Brunton’s person, much less a stiff collar and a waistcoat. I mention this because I had always thought white men insisted on wearing these things. He offered me tea and let me talk for awhile. The result was that I was installed-after twenty minutes-as his “literary and personal secretary.”

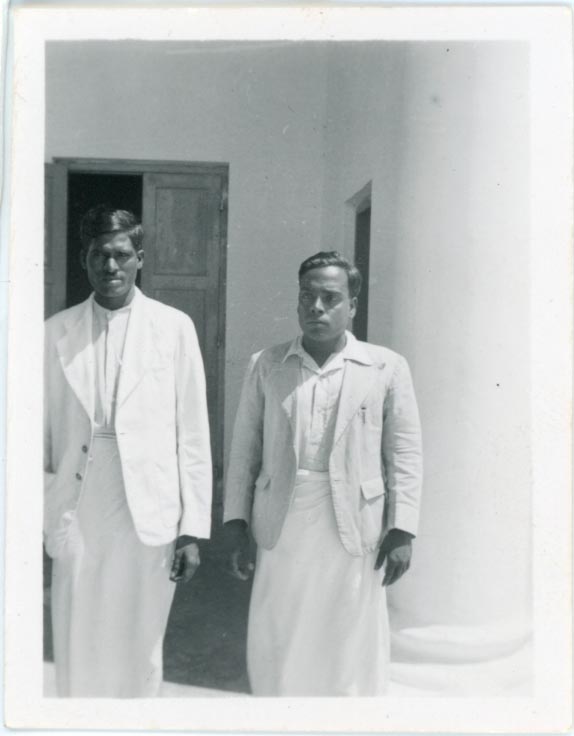

S.S. Gopalkrishnan and a man stand outside a building.

From the Paul Brunton Archives

The house was purely an Indian-style small bungalow with a big courtyard in the middle. No carpets covered the naked rough-bricked floor, no wallpapers adorned the ill-plastered walls, no tapestries hung over doors and windows. There was not even one glass-paned window. The rough wood doors, without paint or varnish, creaked on their hinges. Three small tables, two chairs, an easy chair of light wood and canvass and a small one-doored cupboard besides a cot, all of the camp-folding pattern, were the only furniture to be found. We were away from the noise and din of the bazaar in the surroundings most suitable for literary work of a high and concentrated nature.

For the first few days I was unpacking trunks, getting things straight, and carrying books into rooms. I had to fix up Indian maps on walls, arrange the office, knock nails into walls, move suitcases and dressing cases into their proper places, make many bazaar purchases, and do dozens of other little jobs. Then we opened up a packet containing dozens of unanswered letters from all over the world. They were in different sizes, shapes, colours, and even languages; they were typewritten, pen-written, and penciled. They bore dates stretching back over all the dates in the calendar for more than a year. P.B. was apologetic for this last fact but said his life being what it was, he could not help it.

His cook and personal servant was in some way not unlike his simple-living master. He was a lean chap talking hardly any English. One yard of plain white sheet round his waist and one shirt were all his clothing. This has to be compared to the stylishly dressed butler who usually serve Europeans in India. In spite of his poor appearance he was a cook of no mean kind, for as I came to know later, he had served his master faithfully for nearly six years, and had travelled in many parts of India with him. The secret of his success was that he made the best-tasting soup, the best curried vegetables, and cooked the finest rice. One wondered how such delicious things could come out of that medieval kitchen at the back of the house. If he were not watchful for a single minute, the food-whether raw or cooked-would be stolen away by the innumerable monkeys. In fact, once I saw his master projecting himself from out of his office like a bullet from the gun in hot pursuit of a monkey which had just stolen and was carrying off a typewriter ribbon from his table!

One day P.B. told me abruptly that he had decided to move away from this little town, that his work there had come to an end, and that everything had to be packed and all local matters disposed of within twelve hours; I could never have managed the removal so swiftly before I entered his service but the training in efficiency, concentration, and initiative which I absorbed from him every day enabled me to do it then. We spent a week in the capital city of Madras, and then a telegram came and we were off again to the interior of the country. We became guests of the ruling prince of an Indian state. Some officers of the state met us at the station and conducted us, in two fine motor cars on a fast smooth drive by drivers in gorgeous livery, to a fine palatially fitted-up bungalow. P.B. was then a socially busy soul. State dinners, tea parties with rajahs, and private palace conferences were the order of the day. From the village to the town, from the house to the palace, from the bullock cart to the saloon car, from a small looking-glass held between the fingers to gorgeous wall mirrors, what a change! It can only be imagined. Out flew dinner coats, polished boots, felt hats, walking sticks, white collars, etc. and soon P.B. was completely transformed. Even his conservative secretary with leg-cloths and shirt was moved and got into a pair of trousers and wore a collar and tie. The whiz of the electric fan and the gentle ring of the telephone bell replaced the primitive arrangements of our former home. This sudden change was typical of many which we made in the following years. I was at first surprised but later accustomed to the ease with which P.B. adapted himself to all kinds of environments and people. He passed from palace to hut or vice versa with perfect smoothness and yet with complete inward indifference. He disliked the formal conventions but submitted to them when necessary. He detested public functions in his honour and never attended them if he could avoid doing so. External appearances never weighed with him nor deceived his sense of spiritual values. He never forgot or lost himself whatever the surroundings. He lived in the world when fate or duty called him but was not of it.

S.S. Gopalkrishnan and another man standing outside a tent.

From the Paul Brunton Archives

My secretaryship filled my days with an interest I had not known before. Secretaryship indeed! It was like twelve different lives in one. Handling an international correspondence with five continents in one hour, superintending the cook and servants and bazaar purchases the next, keeping away undesired visitors, plunging into meditation at intervals, walking with him each night after dinner for two miles through city, village, or jungle gravely discussing spiritual questions or joking about the daily events, meeting maharajas one day and poor coolies the next-such was my bewildering unusual life. I repaired our typewriters and fountain pens, invented office equipments from primitive materials, aye, even picked open locks without using keys, as when the keys disappeared to my master’s big steamer trunk in which he placed all his money and important manuscripts, documents, notes, and papers. To his pleasant surprise I successfully opened the locks without injuring them. Such a curious mixture of abilities am I! I was taken raw and uncouth, just over thirty years old, and he trained me on modern lines, made me discard my old-fashioned piece of long untailored cloth that did duty for clothes, gave me jackets and trousers and neckties, etc., and thus transformed my outer appearance. But the change was equally great in my inner life. The typing of his literary notes, the instructions he conveyed to his students in his letters, the books which he presented to me now and then, as also the personal guidance and advice he imparted to me-all these created a new outlook in my life. Certainly, I now know I have not lived in vain.

Our mornings were usually spent on some kind of writing work. P.B. seldom dictated his literary work but preferred to write the first draft himself, seated alone in his office or, at those times of the day when the sun was less hot, seated on the flat roof of the house where he could be away from everything and everybody. I would then copy this draft neatly on the typewriter and he would rewrite it again at his leisure, after which I would again copy the result. On his writing desk he always kept a bronze lotus-throned figure of the Buddha, which had been presented to him by the chief Lama of Siam. It was a symbol for him of the teacher of esoteric wisdom, the sage who typified compassion for all creatures. This solemn-looking and deeply-calm Buddha watched with pious interest and perhaps some sympathy the living man who sought in a very humble way to imitate him. But in the case of his mail, speed in handling was so necessary that he called my assistance to take down in shorthand what he had to say to the readers, students, and friends with whom he tried to keep in touch but always in vain, for he was always in great arrears. He usually retired to the comfort of his bedroom to attend to his mail. There, upon his snug bed, with its coloured counterpane, a large mass of this correspondence spread out on his lap and all over the bed, he squatted with open shirt and cotton trousers, and dictated paragraph after paragraph in reply. I sat in a chair, business-like with a folded turban on my head and squeaking large brown shoes on my feet! My blue fountain pen scribbled rapidly over my notebook. I must not forget the small tray of toast and tea placed at P.B.’s side-that brown nectar which he drank quite often but which was almost harmless because it was quite weak too.

Thus the preliminary chapters of a new book got themselves shaped or, as the metaphysician would put it, were “manifested with name and form” whilst letters were shaped out for the more fortunate of his numerous international correspondents. A week’s mail went out to every corner of the world. After mornings’ business was over, there followed lunch and a short siesta, then reading newspapers, periodicals, or books, whilst half-resting on the bed in the fierce afternoon heat, next interviews with visitors, then the formal tea and toast and then P.B. set to further work, usually on research notes or literary material. Records of interviews and the results of his meditations were also scribbled down. He has filled more unpublished notebooks with his discoveries, ideas, reflections, and intuitions than published printed books. I collected these odd pieces, arranged them under proper headings, and typed them suitably into his leather-bound loose-leaf notebooks ready for future reference. Thus were the religious, mystic, yogic, and philosophic lores of the ancient East brought to light and probed into to their very depths. Thus, too, was P.B.’s keen ever-active intelligence made to yield its fruits, his swift intuitions flashed into words and his profound meditations directed to an amazing variety of matters directly or indirectly connected with humanity’s spiritual life.

S.S. Gopalkrishnan

From the Paul Brunton Archives

After dinner we generally went for a walk to get some exercise. P.B. always carried his walking stick whilst I always carried a pocket electric torch to save us from treading on any possible snakes or scorpions. Sometimes we went into the forest but more often into the lonely roads on the outskirts of the town. Both of us were short figures, but whereas he was slim I was sturdy and prided myself on being able to act as his bodyguard should it ever become necessary.

Lastly, after the day’s activities had ended, but before dinner, there came the real life and secret of the man. He went out on the open upper verandah, squatted on a carpet, and was lost in deep meditation for nearly an hour. Meditation, calm and serene at dusk and under an oriental sky, is a thing which can better be experienced than described. His secretary often joined him, although only in keeping with the old adage that a turkey fowl saw a peacock dancing and thinking himself equally beautiful began to unfold its feathers. Or else we would retire, when the need of greater privacy became heavy, to P.B.’s own room and bolt the door from inside. He would then place a green crystal Buddha-head which he brought from China at the far end of the room and switch on the tiny electric bulb which was hidden inside it. The head emanated a phosphorescent greenish light and the eyes appeared mysteriously alive. The whole room had an unearthly subdued light. In its serenity and silence we easily fell into calm, deep, and concentrated meditation.

I wonder how many people realize how absolutely necessary this meditation is for P.B. when such great pressure constantly devolves on his mind in his attempt to encourage, uplift, and enlighten so many individuals as well as the world at large? On occasions, with the magnetic and telepathic influence of P.B. strongly felt, I sometimes forgot all my personal limitations and flew to ethereal heights, leaving my physical moorings in the body and soaring into vast space, with a feeling of oneness with all the universe. My feeble experience was only an echo or reflection of P.B.’s swift winking into an even deeper state. Such joint meditations destroyed all the worries and miseries of life, and brought great peace to my mind and went a long way to develop me spiritually. And a hundred times more was this so when in the immediate presence and under the guidance of P.B.

Shall I try to describe to the best of my ability and powers of expression and, as far as I can remember, what happened on one of these nights? I shall not add or take away any idea or thought. I describe it exactly as it appeared and happened to me. It is still fully vivid to me because it is still unforgettable. When late engagements or pressure of work made the evening meditation impossible, it was postponed to midnight. That night at 12 o’clock I went and squatted in the open terrace on a carpet spread on the floor, with P.B. at my side. I began to meditate. When the preliminary portion of slowing down the breath and thoughts was over, I very slowly turned my head to the right, to catch a glimpse of the marble statue-like figure there and inwardly drew some inspiration and strength to carry on in earnest the analysis of the ego or “I-thought”. When that was over I slowly turned back to my original position. I often used to feel sleepy on previous occasions owing to the lateness of the hour. But now I was full of life and energy. With one concentrated thought of all-absorbing force I mentally asked, “Who am I?” Then I felt that I was not the body. I said to myself, “If so, try to forget the body.” A kind of dizziness grew over me and my body appeared to become rigid. I slowly began to feel no sensation in it. I could not move my limbs. Am I sleeping? I thought, “no.” I was fully awake. My head and mind alone seemed to be present. All the portion below the neck seemed to melt away. I tried to open my closed eyes. I was not aware of anything in front of me. The parapet walls and the climbing plant were not there. I saw nothing but space. My mind was soaring high. “What am I?” This question alone remained. I felt I was a mere speck floating in the space, invisible to the eye, having no weight or shape or size, a mere idea or thought, a mere nothingness, but still distinctly conscious. No name, no body, nor anything belonging to this world. I was in that state for a few minutes. Then I slowly became aware of breathing and again became conscious of my body. I came back to myself by degrees. I opened my eyes-yes I could see everything plainly, slowly, but with some pain I turned my head again and saw P.B. He was still in a fixed position. A few seconds more, I moved and shook my body, and then got up. The time was a half hour past midnight.

Soon after, we retired to sleep but not before I told P.B. that I had had a very good meditation. Once in bed I wanted to get back that state. I wanted to watch at close quarters what happens when one passes from waking to the sleeping state-to study well the transition as P.B. had written in his notebooks about the importance of this moment. I lay awake for some time, but soon after I must have slept. When I became conscious of myself, a peculiar form or force or energy seemed to flow everywhere, and on all sides, filling up all space and making everything lose all solidity and shape. The whole of the massy building, the walls and floors seemed to melt like butter over fire. I was lost in that ocean of energy. My body, too, seemed to become pliant and flexible, ready to melt away into nothingness. I got frightened. When my heavy body, which had been so solid and real, when 130 pounds of flesh, blood, and bones were vanishing into nothingness, the horror could only be imagined. I was faintly aware that P.B. was sleeping on a bed in the adjacent hall. I called him by name. I heard no response. I tried to get up and did so with difficulty, as the floor under my feet was soft, and I began to sink, as one would sink in thick snow. I called again, but to no purpose. My voice was leaving me. I went to the switch. I switched on the lights but the whole of the electric installation appeared to have lost its solidity. I fumbled on my table and found my torch. I worked it. It also did not burn. There was no light except a star-like kind. Terror became hundredfold. Had the judgment day come or had the dissolution of the world set in? With one great effort, all the effort I could possibly gather, I waded and moved to where P.B. was sleeping. All the five senses were present in me only in part. Very near his bed at the top of my voice I called his name. He awoke and sat up and said something. I could not hear distinctly for hearing, sight, and feeling were ebbing fast out of me, but I felt he seemed to say, “I am here. Do not be afraid.” Then I forgot consciousness, and slowly the whole thing vanished. I do not know how I got back to my bed.

When I awoke it was dawn and the time was 6 A.M. My first feeling was to see my body and to feel sure it had not melted away. I ran my hands over my face and chest. I was again myself. I got up. When questioned, P.B. replied that I had come, terrified, to him during the night, about forty minutes after we had retired.

I tried to find out the changes, additions, or alterations to my thoughts because of this experience. First and foremost, to my mind, this occurrence was a real mystic experience, showing a glimpse into the Absolute and revealing the great truth that the whole world is only an idea. I had read such a thing in P.B.’s notebooks. It was now brought home to me as a piece of strange experience – this empty mentalness of the world. This indeed was how P.B. explained it to me the next morning after it happened. I felt then very strongly that my close association with him was partly responsible for it.

His Indian enemies have described him in their public press attacks as a “journalist in yogic pose.” The truth is that I found him to be really a yogi in journalistic pose! He used to smile indulgently at their attacks but thought it beneath his dignity to answer them. I, however, was not always able to keep silent over such gross injustices and misunderstandings.

He never claimed to be anything more than a student of philosophical mysticism. But many incidents showed how humble was this estimate of his own powers. I may mention a little one. One day it struck me that I should present P.B. with my grandfather’s copy of the book Vishnupuranam translated by H.H. Wilson, a rare edition, one hundred years old and a large volume weighing several pounds. For two days I had not time to talk with P.B. about my wish, but when I did mention it he replied that the past two days he had a great desire to procure that very book. He produced his pocket diary and to my astonishment the entry was found in P.B.’s own handwriting: “Get Vishnupuranam, translated by H.H. Wilson.” He put it down to the fact that he had concentrated on the idea, which went out and found the nearest mind which could be attuned to his. I was overjoyed at his words, and immediately wrote an urgent letter home, got the book through the post, and presented him with it. He was equally glad to accept the same from me as a gift and promised to keep it all his life.

Here is another incident. On the sixth day after I began to work for him, he suddenly predicted that I would stay with him for some years and then go into the employment of a public company which he named, where I would hold a high position. What he foretold was fully realized by later events. If today I am the well-paid confidential secretary and right-hand man to the managing director of one of India’s large pioneer industrial companies, with a brilliant future in prospect before me, it is fair to say that I have been able to accept and carry on this highly responsible post only because of the confidence, courage, discipline, training, and mental development which the work with P.B. continually gave me. And if I have kept my spiritual life fresh and undimmed amidst such a busy and active environment, it is also fair to say that it was P.B. who showed me how to attain and keep such a difficult balance. Despite the passing of years, my loyal feelings toward him remain unchanged. He is living at a great distance from me now, but not from my mind and heart.

4936 NYS Route 414

Burdett, New York 14818

USA

© 2024 Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation.