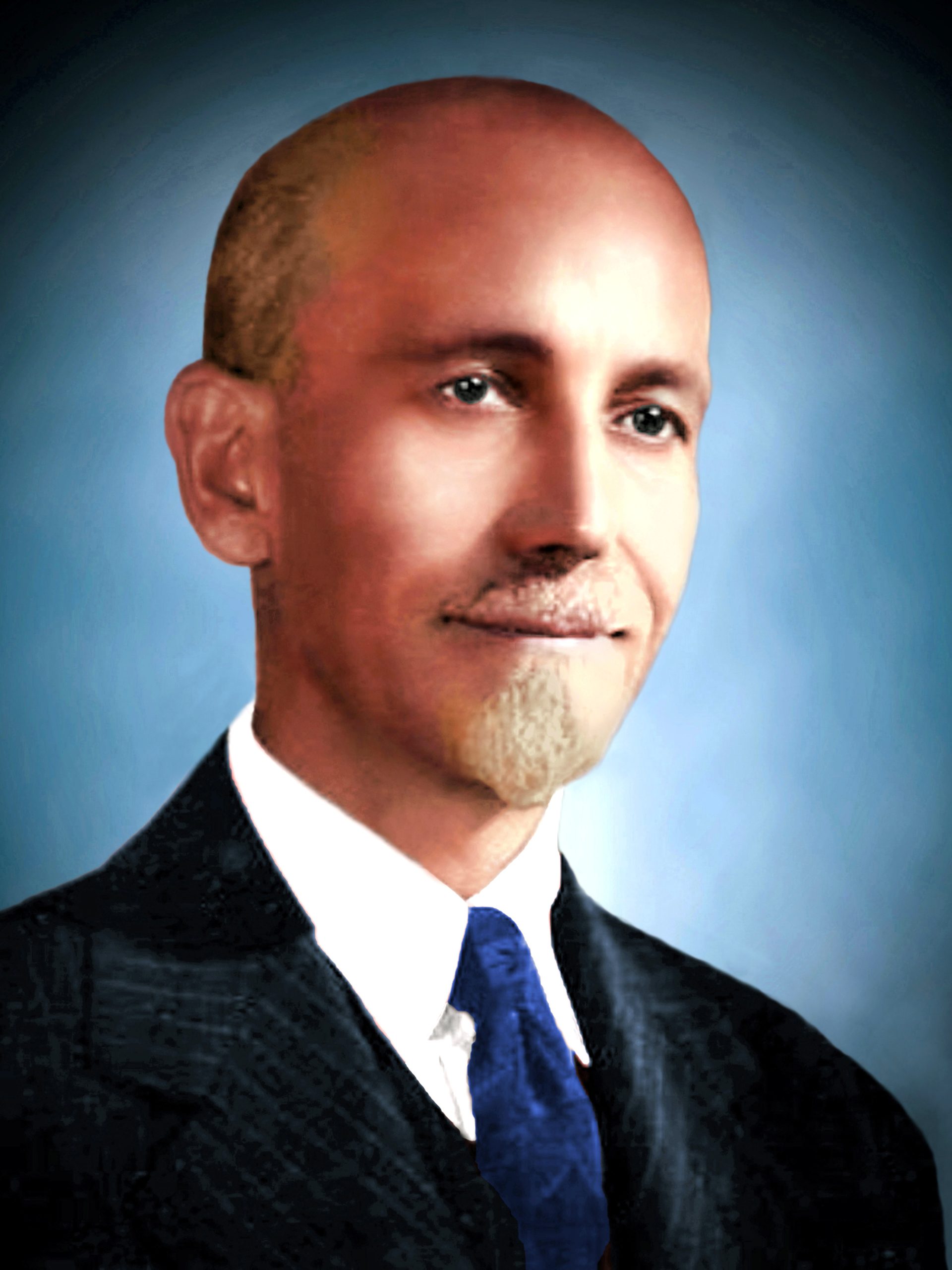

Paul Brunton (1898-1981) devoted his life to the practices, understanding, realization, and sharing of spiritual truths. During his public life he wrote eleven books and lived on every continent but Antarctica—and no doubt would have visited there, were a saint or sage known to be in residence! He also wrote daily thoughts in little notebooks, interviewed hundreds of teachers, fakirs, “fakers,” and saints around the globe. While he discouraged people from becoming his followers, inevitably many who encountered him became students of his. For those fortunate individuals he offered his counsel and guidance when and where it was appropriate. (For example, when someone asked him to bless his new restaurant, his response was, “I can bless your enterprise, which will help you learn a spiritual lesson from the endeavor, but if you want it to be a success, I suggest you ask the advice of a businessman!”)

As Brunton grew in spiritual stature, he was increasingly inclined towards anonymity, so much so that by the time he reached full illumination (the state known in India as “sahaja”) in the early ’60s he was practically forgotten by the public. As much as he disliked “the cult of personality,” he treasured the free and open circulation of the deepest, most precious teachings the world has to offer. To this end he committed his life to the task of creating a spiritual path suitable for the fast-paced world of the 21st century—a path that we now have before us in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. In these remarkable volumes you will find a blend of his own inner insight with ancient traditions and contemporary teachings—a philosophy in the best sense of that word: “love and wisdom” combined, leading us ultimately to the Wisdom of Mind Alone and to the Love of our own higher self, the Overself.

Paul Brunton’s life organizes itself into four different phases: his beginnings, his early notoriety as an Orientalist, his focus on modernizing the perennial philosophy for the West, and his final years immersed in the impersonal silence of Mind. To measure any philosopher by their beginnings is a mistake. It is not so much how they start, nor even how they end that matters; their truth is to be found in their journey and in the teachings by which they stand. Brunton himself came to this insight in the 1940s when he abandoned his Search in Secret… series and turned his mind—and pen—towards the greater heights of epistemology and metaphysics. To dwell upon his childhood and his youthful efforts is tempting, because these are the phases we ourselves can relate to without much effort; to direct ourselves towards those loftier heights requires more attention and effort. That effort will reward us with insights into our own Selves and into the ecstatic austerity of Truth.

So, let us briefly consider Brunton’s life, starting with his birth. As soon as we do so, we encounter his own strong penchant for privacy: throughout his life, PB, (as he came to refer to himself later), gave out his birthday as 11/27/1898; a brief search of the Internet will produce a second date: 10/21/1898. PB said that there were two reasons he gave out a false birthday: political and occult. During the end of the British Raj both the British and Indian governments suspected him of spying for the other side—an activity he had no interest in. He therefore took the measure of traveling under his “nom-de-plume”—including a new birth-date! The other motivation has to do with the dangerous meddling with magic and the occult prevalent among seekers during his early years as a well-known figure in mystic circles. He little cared about the biographical significance of his birthday, but cared very much indeed that his horoscope not fall into unfriendly hands; to this end he continued to refer to the November birth-date throughout his life. Nonetheless, when his son was asked his birth-date, he stated that it was October 21, 1898. Henceforward, we shall refer to this latter date as his birthday.

So: the individual that we came to know as Paul Brunton started out life as Raphael Hurst in London on October 21, 1898. He grew up in the Cockney section of London and lost his mother while he was still quite young; his father remarried, and his new wife brought her sister and the ideas of Christian Science into the family. PB later commented that one of them was a very successful Practitioner who was able to heal herself and other people as well, while the other suffered health problems her whole life. Perhaps this clear evidence of the power of mind over matter, and also the obvious failure of this same ‘law’ contributed to PB’s interest in the occult and in gaining a deeper understanding of the truth of the laws that govern our existence.

The next we hear of PB is from his own hand, when he tells us, “Before I reached the threshold of manhood and after six months of unwavering daily practice of meditation and eighteen months of burning aspiration for the Spiritual Self, I underwent a series of mystical ecstasies. During them I attained a kind of elementary consciousness of it. If anyone could imagine a consciousness which does not objectify anything but remains in its own native purity, a happiness beyond which it is impossible to go, and a self which is unvaryingly one and the same, he would have the correct idea of the Overself…(Notebooks 12.1.2).” This was around his sixteenth year, which would have coincided with the commencement of WWI in 1914 (PB served in the tank corps 1917-18). By the time he was in his early twenties he had become actively involved with like-minded souls interested in exploring the obscure, the occult, and the mysticism of the far East.

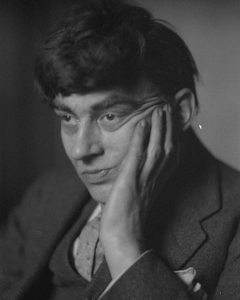

It was during this time that Paul Brunton met his three early teachers: Charles Henry Allan Bennett (pictured right), also known as Bhikkhu Ananda Metteyya; the unnamed Indian who PB refers to in the opening chapters of A Search in Secret India as “the Rajah;” and an American painter named Thurston, who was also involved with the Occult. Characteristically, PB never spoke much about “the Rajah” or Thurston—very probably at their own request. We do know that his son, Kenneth, was given his middle name, Thurston, in honor of this mysterious painter.

Allan Bennett

Theosophical Society emblem

PB briefly joined the Theosophical Society (Adyar, America), and during and immediately after WWI he attended many gatherings in London that a plethora of active occult groups held. Through his apprenticeship with Allan Bennett, he was aware of the activities of the (Hermetic) Order of the Golden Dawn, of which Bennett was a significant member. He made many friends and, with his pal Michael Houghton, even ran a bookstore, which unfortunately failed within months of opening. During this time, the two friends rented an apartment in Tavistock Square (pictured right), which was fated to house a more successful publishing enterprise a few years later: the first home of The Hogarth Press, run by Virginia Woolf and her husband. In 1922 Houghton opened The Atlantis Bookshop in Bloomsbury, which is still in operation today. In 1927 Houghton wrote and published The White Brother: An Occult Autobiography under the pen-name Michael Juste, which centers on a character called “David,” loosely based on Brunton.

At the age of 24 Brunton married Karen Tottrup (pictured left), and his only child,

At the age of 24 Brunton married Karen Tottrup (pictured left), and his only child,  Kenneth Thurston Hurst (pictured right) was born the next year, in 1923. That was the year that he also lost Allan Bennett, who died at the age of 51 after a lifelong battle with poor health. A few years later the marriage came to an end, and thereafter their son Kenneth was raised by his mother and his step-father, Leonard Gill. PB stayed on amicable terms with the family, and, as Hurst’s book Paul Brunton: A Personal View indicates, in due course his son became one of his students. It was during this period—and hardly surprisingly, given the external changes in Brunton’s life—that the allure of the purely occult soon faded and he sought to journey into the deeper waters of mysticism and from thence into philosophy. This search led him away from England and into the then-uncharted world of the Sacred East.

Kenneth Thurston Hurst (pictured right) was born the next year, in 1923. That was the year that he also lost Allan Bennett, who died at the age of 51 after a lifelong battle with poor health. A few years later the marriage came to an end, and thereafter their son Kenneth was raised by his mother and his step-father, Leonard Gill. PB stayed on amicable terms with the family, and, as Hurst’s book Paul Brunton: A Personal View indicates, in due course his son became one of his students. It was during this period—and hardly surprisingly, given the external changes in Brunton’s life—that the allure of the purely occult soon faded and he sought to journey into the deeper waters of mysticism and from thence into philosophy. This search led him away from England and into the then-uncharted world of the Sacred East.

It was also in this period that Brunton established himself as an avid vegetarian and meditator. These two practices were fundamental to his lifestyle and shared the rare distinction of being disciplines about which he was unequivocal. On practically every other discipline associated with spiritual development, PB tended to emphasize balance and commonsense, and he gave advice based more upon the individual’s needs than any hard and fast rule. PB preferred a vegan to vegetarian diet, and kept to his British roots by preferring tea over coffee most of his life. As he aged, his preferences became very subtle, with a tendency towards lightly steamed vegetables and mild green tea, but sometimes he’d break out his stash of 4-alarm Madras Curry and complete the meal with a large piece of chocolate!

As he traveled through the Mid- and Far-East, Paul Brunton interviewed literally hundreds of mystics, gurus, teachers, fakirs, and magicians; basically anyone involved with exploring the worlds of spirit and mind. He did so without prejudice, and was only critical of those full-fledged mountebanks that fed upon the gullible and innocent. Gradually his attention came to fully rest upon the Indian Sub-continent, where he undertook to find a spiritual master from whom he could learn the path to enlightenment. That journey is largely chronicled in his popular book A Search in Secret India, which describes his arrival at the doorstep of Sri Ramana Maharshi (pictured below) and his time at the feet of that revered sage.

Through his studies with Ramana, Paul Brunton mastered the “Who Am I” meditation and thereby achieved a deepened degree of self-awareness. He was not satisfied with this, however, as he wished to understand the “Why” and “How” of this technique; this led him to the experts of Vedanta such as V. Subramanya Iyer with whom he studied the classic literature of Hindu philosophy such as the Ashtavakra Samhita, the Bhagavad Gîta and the Mandukya Upanishad. It was during his conversations with V. S. Iyer that PB began to develop his own non-sectarian vocabulary for basic spiritual principles. Thus he began to write about the “Overself” in lieu of Adhyâtman and Soul, “World Mind” instead of God or Îshvara, and “Mind” instead of Brahman or The One.

V. Subramanya Iyer

This change marked the end of PB’s apprenticeship and the beginning of his own truly independent journey. That journey took him deep within himself and continued to lead him all over the world. Over the next few decades, in addition to India, he visited China, Mexico, the United States, many countries in Europe, Egypt, Japan, Ceylon, Thailand, Cambodia, New Zealand, and Australia (there may be more). His account of some of his travels can be found in his two remaining travelogues, both published in 1936 (as was A Message from Arunachala): A Search in Secret Egypt and A Hermit in the Himalayas, as well as in vol. 8 of The Notebooks, and in his literary archive, where he continued to chronicle his interviews in the West as well as in the East. As he traveled externally and internally, the driving force of his life became the call to deliver the hidden mysteries of mysticism and philosophy into the hands of modern seekers, stripped of all unneeded hyperbole, jargon, obscuring esotericism and outworn requirements.

As he says in his notes, “The age of esotericism has come to an end, and the age of open teaching is upon us.” (Notebooks 20.2.3) To this end, PB translated the elaborate teachings of India, Tibet, and China into a streamlined collection of central points and practices designed to give spiritual seekers a solid foundation for all their seeking, regardless of where it took them. He took the ancient meditation practices of the ashram and modified them to suit the schedules of the modern city-dweller. Some ancient practices were designed to open our sensitivity to our surroundings—which is fine if one is living in seclusion, but is hardly viable in today’s nerve-jangling urban landscape, so Brunton wrote about those meditation techniques that soothe the nerves and protect us from the extroverted world that most of us inhabit. These meditation practices can be found in The Secret Path, The Inner Reality, The Quest of the Overself, and in Volumes 4 and 15 of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. The Inner Reality (1939), latter named Discover Yourself, was written as a bridge between Eastern and Western faiths. Then he turned his attention fully to the task of presenting the fundamentals of a genuinely spiritual philosophy in a modern language—and in the first language to have a nearly worldwide presence: English.

Brunton was one of the first authors to subject Eastern doctrines to the methodology of science while also challenging science to look beyond its technology and into the true mysteries of life. He wanted to link science and mysticism, and generally integrate the accomplishments of Western Philosophy with the insights of Hinduism and Buddhism. The first result of this effort was his 1938 Ph.D. thesis (Indian Philosophy and Modern Culture), published by Rider and Co. in the United Kingdom & E. P. Dutton and Co. in USA in 1939, followed by The Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga, published in 1941, which addresses the issues of epistemology through the double lens of modern science and the reasoned enquiries of the ancient East. He then completed this project two years later with his metaphysical opus, The Wisdom of the Overself. His later thoughts on these topics are to be found in Volume 13 of his Notebooks series. Curiously, he once again found himself sharing space (if not time) with another author: in this case, the apartment in which he wrote these texts had once been occupied by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky when she was writing her great work The Secret Doctrine. “So PB was following after HPB,” he once half-jokingly quipped.

It might be worth pausing for a moment here and taking a look around at the world in which all these books were appearing. While some of us (Americans) think of World War II as starting with the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the reality is that by then the war had been going on in Europe for three years, and Hitler had been in power in Germany for eight, during which time the atrocities against the Jews, Gypsies, and others were well-established protocols of the German Reich. Indeed, by the time The Inner Reality was in bookstores, the people of Great Britain were experiencing nightly air-raids from the German Luftwaffe, resulting in widespread chaos and loss of life. Of late, America has been traumatized by one such bombing; in those years such an event was a daily, if not hourly, event. Consider then the strong need the people of those times felt to find an explanation for the suffering and chaos around them and to find any means of coping with the un-imaginable horrors and uncertainties of their surroundings. The presence of death, evil, and doubt overshadowed all aspects of life and all levels of society. No one was immune, and no one could be oblivious. To find in these books, then, direct and reasoned confirmation of what everyone needed to know—that we do survive death, that there is divine, albeit impersonal, presence to be found here, and that life has both an immediate and a transcendental purpose—was spirit-saving. This was PB’s inspired contribution to the world—a contribution that remains relevant today.

The three books, The Quest of the Overself, The Hidden Teaching, and The Wisdom, cover mysticism, mentalism, and metaphysics and thus lay the groundwork for one’s independent inner journey towards—and beyond—the Higher Self, the Overself. Starting with the requisite understanding of ourselves and how our minds work, PB then guides us into the full mysteries of Absolute Mind and its outward, creative aspect, the World-Mind. To those familiar with the great thinkers of Hinduism and Buddhism, many of Brunton’s points will be quite familiar; their value, then, is in their dogma-free presentation. You can reliably study these texts as an eclectic, or as an orthodox seeker; they are meant as “user’s manuals” to the immediate and transcendent Reality of which we can and may be a part. In every case, Brunton wanted to inspire and stimulate his readers to deepen their own search and to think for themselves. He did not wish to have disciples or establish a “Brunton movement,” to the extent that he preferred that his editors maintain focus on the ideas and issues of philosophy, not his own (truly) charismatic personality.

After completing these books, Brunton continued to travel the globe (you should have seen his suitcases!) for the next two decades before eventually settling in Switzerland. During that time, PB continued to write, lecture, and give personal interviews throughout America, Europe, Asia, and Australia. His final book, The Spiritual Crisis of Man, was published in 1952, after which time PB reserved all further notes for posthumous publication. He married Evangeline Young that same year, and they remained married until his inner work once again required a period of near-absolute solitude. Even so, once that work was complete, PB maintained an active relationship with Evangeline and her family, right up until the last days of his life.

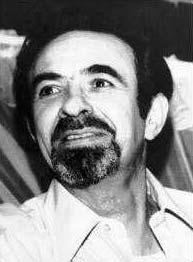

Anthony Damiani

It was also during this time that his son, Kenneth Hurst moved, to America, and PB came into contact with one of his most important students, Anthony Damiani in New York City, as well as Roy Burkhart in Columbus, Ohio. The eventual outcome of both these meetings was the formation of study groups in New York and Ohio. Another group was formed in Czechoslovakia during a time when owning a spiritually oriented book was a dangerous choice. At last it came time for Brunton to withdraw from the world to fulfill his inward journey. This required his isolation from nearly all who knew him and took him to Australia and New Zealand for a few years.

When the final spiritual crisis had passed, the ego was defeated, and thereafter the spiritual wanderer took up his “celestial address,” as Anthony often put it. This was no idle remark on Anthony’s part: Paul Brunton achieved that extraordinary state called “Sahaja” by the Hindus. As he himself put it, the state of Sahaja is not one of knowing reality, but one of being reality—in other words, of being Realized. When Anthony said that he had a celestial address, what he meant was that PB had relocated his identity from the transient realm of manifestation to the eternal realm of being.

With this increased impersonality, it became more natural to refer to him as PB rather than “Paul Brunton,” for there was little of what we commonly experience as a person or personality present in him. Indeed, when in the presence of the powerful silence around him, this abbreviation seemed only natural, as there was an overwhelming air of ‘other’ around him, a remoteness that was sometimes quite unsettling. At other times he radiated a kind of benign peace that drew strangers to him. For example, when he was in the hospital for a minor surgery, I [Timothy Smith] came to his room at sundown only to find the room packed with the nurses, orderlies, and other hospital personnel who “just liked being around him” as he sat in contemplation of the setting sun.

Although PB had standing invitations to live in America and other parts of Europe, he settled in Switzerland, which was due in part to his love of the countryside and in part also to its political significance. Over the years of his long life he lived in Lucerne, Zurich, Montreux, and Vevey, and his final residence was in the tiny village of La Tour de Peliz. Although retired from the public eye, PB continued to keep close watch on the events of the world, and his choice of Switzerland allowed him discrete access to various politicians and world leaders as they came and went from Geneva.

Even after PB announced his retirement, he continued to receive his students and write in his notebooks. His other work—his inner researches—he was reticent to speak about. While PB continued to employ simple terms for deep teachings in his later writings, he also pursued his studies and investigations into the many traditions and doctrines of the world. During his last years he was in contact with both His Holiness the 69th Shankaracarya and His Holiness the Dalai Lama, while his bedside reading consisted of Plotinus, Maritan, scientific journals, occult quarterlies, Jesuitical articles, Tibetan texts, and the Upanishads.

Paul Brunton died on July 27th, 1981 with Paul Cash and his son Kenneth Hurst by his side. He died as he lived: peacefully, privately, and with an ironic smile on his lips. His literary effects, several shelves of notebooks, were willed to his son Kenneth Hurst, while responsibility for deciding what to do with these writings was given to Anthony Damiani’s students Paul Cash and Timothy Smith (both of whom had functioned as secretaries for PB in his lattermost years). At first the task of sorting through these notebooks and the stunning ideas contained within them was guided by PB’s central student, Anthony Damiani; sadly he died only a few years later himself, but did survive long enough to see the publication of Perspectives, accomplished by the tremendous volunteer forces of Wisdom’s Goldenrod and the generous support of Larson Publications. A few years later the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation was formed to ensure the complete publication of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, and to generally present the public with the ideas found in PB’s writings. The task of getting the Notebooks out took hundreds of hours from over forty volunteers and lasted from 1980 through 1989. Since then the PBPF has devoted itself to furthering the ideas and outlook of PB and supporting those around the world who find their way to his remarkable works.

In the end, we cannot tell the story of Paul Brunton, nor should we do so. We who would ask should—must—acquiesce to his repeated admonitions that we direct our full attention to the varied aspects of a meaningful spiritual life and eschew the cult of personality. Even as Ramana Maharshi rebuffed all questions with the appropriate instruction to first find the “Who Am I” before all else, so with PB we should first understand his written words, starting with A Search in Secret India and concluding with the extraordinary Notebooks series. These teachings, like those of all great philosophers, will long outlast the story of his life, and the truths upon which both are based are directly available to us all, should we have the dedication, training, and Grace to come into their orb.

4936 NYS Route 414

Burdett, New York 14818

USA

© 2024 Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation.